Another sample from Not Your Usual Science. Be patient... I got side-tracked to do an essay on poisons (one of my favourite topics) that looks like turning into a book.

So since we are talking about writing, there were a few conditions that would need to be met before

writing caught on. As a rule, nomads would not wish to make or carry around

records, especially when they were written on heavy clay tablets. So people

probably needed something to write on, something to write with, and a useful

place where the written records could be kept. Inscribed stones might appear,

but unless there were other uses, the whole writing thing might be a bit of a

flash in the pan.

The Sumerians explained the invention of writing with a

sort of fairy tale about a messenger who was so tired when he reached the court

of a distant ruler that he could not deliver his message from the king of Uruk.

Hearing this, the Sumerian king took a piece of clay, flattened it, and wrote a

message on it.

That story has a few sizable holes in it. How would the

person receiving the message know what the symbols meant? Then again, what can

we expect in a tale about events that happened so long ago, especially when it

was probably not written down?

|

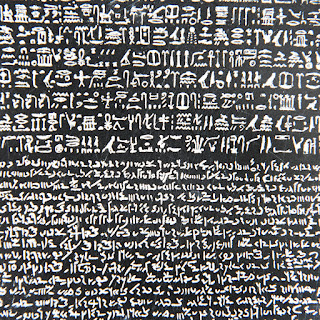

| Hieroglyphs. [Christine Macinnis] |

The Egyptians said the god Thoth (the scribe and historian

of the gods) invented hieroglyphs; the Sumerians either credited the unnamed

king who wrote to Uruk — or the god Enlil. The Assyrians and Babylonians said

the god Nabu was the inventor, while the Mayans said they owed their writing

system to the supreme deity Itzamna who was a shaman, a sorcerer, and creator

of the world.

More plausibly, Chinese tradition says writing was

invented by a sage called Ts’ang Chieh, a minister to the legendary Huang Ti (the

Yellow Emperor).

How many of these can you "read"?

Some writing used characters to represent syllables, other

writing systems used a symbol just to mean a letter-sound (as we do in

English), while still others used a symbol to mean a word or idea, as happens

in Chinese.

These word/idea symbols are called ideograms or

logograms (meaning each symbol is an idea), and they can mean the same thing in

different languages, rather like the signs in airports or the numeral 5. Just

to confuse things, some of those airport signs are also called pictograms,

because they are pictures of what they represent.

Then again, Egyptian hieroglyphs are a mixture of

alphabetic characters and ideograms, with a few extra symbols to clarify the

meaning. Few writing systems were designed from scratch: they just grew, a bit

like English spelling!

The Sumerians lived in what is now southern Iraq.

Ignoring the myth quoted above, their writing probably started with marks on

clay that Sumerian accountants used around 3300 or 3200 BCE to record numbers

of livestock and stores of grain, the sorts of records societies need, once

they start farming. Over about 500 years, the symbols became more abstract,

allowing ideas to be written down as well.

Egyptian hieroglyphs (literally, the word means ‘priestly

writing’) are unlike Sumerian cuneiform. They probably developed separately,

but maybe the Egyptians got the basic idea of marks to represent language from

other people. The Harappan script from the Indus valley in what is now Pakistan

and western India, seems to be another independent growth, though nobody has

learned to read it yet. The civilisation which established it collapsed in

about 1900 BCE, so the script did not develop further.

The oldest alphabets that we know about seem to have emerged in Egypt around 1800 BCE. They were developed by people speaking a Semitic language, and the writing only covered consonants. These variants later gave rise to several other systems: a Proto-Canaanite alphabet at around 1400 BCE and a South Arabian alphabet, some 200 years later. There were others, but we will stay with those examples.

The Phoenicians adopted the Proto-Canaanite alphabet which later became both Aramaic and Greek, then through Greek, inspired other alphabets used in Anatolia and Italy, and so gave us the Latin alphabet, which became our modern alphabet. Aramaic may have inspired some Indian scripts, and certainly became the Hebrew and Arabic scripts. Greek and Latin inspired Norse runes and also the Gothic and Cyrillic alphabets.

|

| The Rosetta Stone solved a lot of puzzles. |

Now the way was open for poetry, literature, history, philosophy, mathematics, recipes, technical information, tax, weather and astronomical records, religious teachings and more to be written down and passed from one generation to another, without the need for story-teller, whose main role was to memorise everything.

Just occasionally,

we can get lucky, but most ancient systems are only ‘cracked’ by intensive

work. Carved in 196 BCE, the Rosetta stone was found in 1799 by French soldiers

fighting in the Napoleonic Wars in Egypt. The inscriptions all said the same

thing, but in Greek, in Egyptian demotic script, and in hieroglyphics. In other

words, for the first time, the mysterious hieroglyphics could be compared with

a translation.

The content is

fairly boring, a list of taxes repealed by Ptolemy V, but the use of three

languages made the stone very exciting. When the French were defeated, it was

handed over to the British, and placed on display at the British Museum in

1802.

The Rosetta

Stone was described by its original French finders as ‘une pierre de granite

noir’, a stone of black granite, but this was not a geologist’s granite. This

term ‘black granite’, conferred in less geologically rigorous times, was applied

200 years ago by Egyptologists to a dark, fine-grained stone from Aswan. The

British have always called the stone basalt, since they gained possession of it

during the Napoleonic wars. Neither description is correct.

Recent cleaning

and a careful examination has shown that the stone was probably sourced from

Ptolemaic quarries to the south of Aswan. Probably nobody cared much what the

stone was, as the important question was the text, not the material it was

inscribed on.

From a

geological viewpoint, though, it is neither a basalt nor a granite, but a

fine-grained granodiorite, perhaps modified by metamorphic and/or metasomatic

processes. For most purposes, we can think of it as a granodiorite, but in

chemical terms, say the researchers who have looked at it, the stone is more

like tonalite.

Granodiorite

has quartz and plagioclase, but it also contains biotite and hornblende, and it

is typically darker than granite. All the same, it is hard to see how it could

be mistaken for basalt, but the secret to the issue lies in the reference to

recent cleaning.

The confusion arose

because the stone has been covered for many years with black carnauba wax,

remnants of printer’s ink, used to obtain contact-prints of the inscriptions,

finger grease and dirt, with white paint in the incised lettering to make it

stand out.

When the stone

was being cleaned in 1998, it became apparent that the stone was not basalt at

all. Work based on petrographic examination and analysis of a fragment from the

Rosetta Stone showed conclusively that it is a granodiorite. To be precise, the

Rosetta Stone is made of a granodiorite that has probably been exposed to some

extra heating. It is not basalt, but it should not be taken for granite,

either.

No comments:

Post a Comment