This gives you a taste for how I tackle each topic in Australia, a Social History, with a great deal of background, and a great deal of mythbusting. I have left out quite a lot of the later pictures, but the captions are there.

7. The Lure of Gold

When it was announced that

gold had been discovered in two Australian colonies in 1851, the rush was on.

Large numbers of people arrived in Australia, with many believing that finding

gold would be as easy as digging up potatoes. Some were lucky, became rich and

took their wealth back home. Others found enough gold to buy a farm and settle

down in Australia. Yet others lost everything, but soon found jobs and stayed

on. Australia’s economy boomed, and life in the colonies changed forever.

Why seek gold?

Once humans discovered metals, gold quickly

became the most important one, but why? It is shiny, it doesn’t tarnish or rust

like silver or iron, but you cannot make useful tools or machines from gold. A

gold bicycle would be too heavy, and it would bend too easily. Besides,

everybody knows gold is valuable, so

thieves would steal any golden bike. There was a gold rush near Prague (now in

the Czech Republic) in the year 760, when so many farmers went chasing gold

that no crops were planted and there was a famine the next year. Australia

could have had famine, too.

Farm labourers and farmers were rare, and on

the diggings, Charles Rudston Read could not get men at 30 shillings a day to

build a rough bush stable. Ellen Clacy heard of a gentleman who was ‘… more

fitted for a gay London life than a residence in the colonies …’. He was

earning more than £400 a year as a house carpenter in Melbourne, 32 shillings a

day, with all of the comforts of town life available. For comparison, Read, who

was a senior official, was paid either £400 or £500 a year, which is equal to

either 32 shillings or 40 shillings a day.

People only wanted to work at hunting the

elusive gold, but why do we think this useless, hunger-making metal is

important?

We say things are ‘heavy as lead’, but lead

has a specific gravity of only 11.35, meaning a one-litre block of lead, a

10-centimetre cube, weighs 11.35 kilograms. Gold, on the other hand, has a

specific gravity of around 19.3 and a similar cube would weigh 19.3 kg. It

would be worth $AUD100,000, near enough. While people will pay that sort of

money, we want gold!

The

gold rushes

Unknown artist, an unlikely depiction of a lucky strike. A shaft, that close to a creek, would soon become a well, and there is no cradle. Pans were used for prospecting, not for winning large amounts of gold.

The gold rushes in Australia began in 1851, but people had

often found, or had claimed to have found, gold in Australia before that time.

So why did it take so long for a gold rush to begin? There’s a story there…

Early discoveries

In August 1788, the first gold ‘discovery’ was faked by a

First Fleet convict called James Daley. This convicted burglar made his ‘gold’

with filings from a brass buckle and a gold coin. He was flogged for this

attempted fraud, and after that people were suspicious of every ‘find’.

In about 1824, legend says an unnamed convict found a

gold nugget on ‘the Big Hill’—the steep slope on the western side of the Blue

Mountains near Hartley. Tradition says he was flogged, so a magistrate must

have decided the nugget was made artificially from stolen gold.

In the 1840s, a shepherd named Hugh M’Gregor often sold

gold in Sydney. Most people knew he got it from the Wellington Valley, which

was on the western edge of where the gold rush would eventually begin. Gold was found in South Australia in 1843,

and it was being mined by 1846. Though the find was not large, it might have started a gold rush but it

did not. Neither did a report in 1847 by a Cornish miner named John Phillips,

who found more gold in South Australia.

In 1849, a shepherd named Thomas Chapman found a large

lump of gold, worth two years’ pay for a shepherd, in the Pyrenees Ranges near

Melbourne. People rushed off to look for more, but they did not know how to

find gold or where the find was made and the police chased them away,

empty-handed. The Victorian government did not want a gold rush in 1849, but by

then news had reached Australia about the gold rush in California, and

adventurous Australians sailed off to America. They

came back knowing how to look for gold and where to find it. All the same, the

rushes might never have happened without Edward Hargraves but the Australian

gold story isn’t quite what you think it is, and there is more to finding gold

than people believe.

Gold

and entropy

Young

physicists always struggle to explain entropy, while older ones with families

grin and say that just like teenagers, Nature always leaves a state of

disorder, on average, greater than it was at the start. Gold deposits are

paradoxical, because science says that in

a closed system, and on average

(and note those careful qualifications!), entropy, or disorder, increases.

This

is the scientists’ way of saying that over time, everything gets more random,

more dispersed. The only way you can reduce entropy and concentrate gold atoms

into a small space is by applying energy, and getting and delivering that

energy increases the entropy somewhere else. When we find order, like atoms of

gold grouping together instead of spreading out, there has to be some other

process going on, some change that increases disorder somewhere else by enough

to be able to cover the entropy-decrease that a gold deposit represents.

On

average, gold is present as about 5 parts per billion in

the rocks of the Earth’s crust. All the same, chunks of gold weighing as

much as 50 kilograms have been found in the past, and such prizes may be found

again—but there probably aren’t many of those big lumps left.

A sovereign minted in 1894, face value $2, price about

$1000 today.

Finding

the elusive gold

There

are two kinds of gold. The easy-to-spot gold is loose alluvial gold, water-washed

gold, that has come out of broken-down rocks. Alluvial gold gets trapped in

creek and river beds, because even a small piece of gold is very heavy. While

sand and mud wash away in running water, even tiny flakes of gold remain

behind, and even tiny bits are worth money.

This

sort of gold is quickly scooped up at the start of a gold rush. After that,

gold seekers need to sift dirt or crush rocks to get the gold out of them, which

is much harder work. Once the rush got going, people hurried off to the

goldfields to gather up the alluvial gold before it all disappeared. But where

did alluvial gold come from, and is there any more?

The

easy answer first: there probably isn’t much more alluvial gold, and it will

take a while to refresh all the water-courses with glittering richness. Gold

begins its time near the earth’s surface as veins in rock that was once molten.

Later, it becomes alluvial gold in streams or makes placer deposits, after the

rocks with gold veins in them are broken down as rocks decay in a process that geologists

call weathering.

We

will look first at how veins form. This is theory, because the chemistry and

physics are hard to reproduce in the laboratory, and the processes involve

vicious, vipering heat and monstrous, crushing pressure. Simulating these

extreme cases would require some very expensive engineering.

The

melting point of gold is a comparatively low 1064°C. Silicon dioxide, the

quartz that often accompanies gold, melts and solidifies at 1700°C. The other

dense metals all have much higher melting points, with osmium and rhenium only

melting at temperatures above 3000°C, so gold’s much lower melting point stands

out as odd. This anomaly may explain how gold deposits form inside rocks.

The

typical vein of gold most probably formed in once-molten rock when liquid gold

stayed liquid, after rock crystals had crystallised out from the molten rock

(you can call it magma if you want to be technical). This is because of the

lower melting point of gold.

So

as the magma slowly cooled, the gold remained liquid, long after most of the

rock minerals had solidified, at which point the liquid gold squished through

gaps in the newly-formed rock. Later, those deposits ended up as alluvial gold

in streams or as placer deposits, but only after the rocks with gold veins in

them are broken down by weathering.

Another

theory says very hot water was involved. As pools of magma pushed up into the

top 8 kilometres or so of the Earth’s crust, they made ground water heat up and

circulate. (Every day, this heat drives the natural hot water and steam systems

and geysers that can be seen in New Zealand at Rotorua, in many parts of

Iceland, and also at Yellowstone.)

Down

deep, it wasn’t just hot water, because the huge pressures stopped the water

from boiling. It became hydrothermal

water, superheated water that scalded and seared through hot rocks, ripping

at them in abnormal chemistry. This fluid was more dangerous than any

dragon—but where mythical dragons guard their gold tenaciously, the real water

(in this model) gave its gold up.

This

super-dissolving, savage water can dissolve the supposedly inert and insoluble

gold in the rocks and magma. Hydrothermal water certainly leaches other

minerals from the rocks, deep underground, dissolving and carrying them up

until, in some cooler place with less pressure, the minerals escape and form

ore bodies. This is a proven fact for some minerals—and it may apply to gold in

igneous rocks.

It

would be nice to know which model is correct, because it would help prospectors

decide where to look, but the scientific jury is still out. Choosing a model

becomes academic when we look at surface deposits, which form because gold is

so dense. When people seek gold in streams and rivers, the veins are ancient

history—and so is the question of how they formed. Where

the gold came from doesn’t matter as much as where it ends up: as alluvial

or placer gold.

Without

alluvial gold, there would never have been a gold rush, because alluvial gold

lies in full view, making it easy to find, if you know how to look. Once people

start to pick the gold up, and sell it, other people start getting hungry for

gold.

Families

headed to the goldfields, often towing a heavy cart loaded with tools, food and

possessions. Each family member was eager to work hard together to win a

fortune—or for the practical ones, at least to get enough money to buy a farm,

animals and seed, with some spare cash to live on until the farm got going. Mainly,

people dreamed of untold riches.

Some

gold hunters succeeded, some lost their money or caught diseases in the

unhealthy conditions on the goldfields, and some died of those diseases or were

crushed when holes caved in. They began with the easy pickings in rivers and

streams, ‘washing for gold’.

Everyone in the family worked hard on the goldfields. The woman is rocking a cradle.

Washing for gold

Washing

for gold can be as simple as picking it from a fast current like the water race

where James Marshall first saw gold in California. A deep ditch like the water

race was inconvenient for ‘washing’, and that was where the cradle came in,

when a man showed Marshall how to make it. People imagine a digger using a pan,

swirling away the last few grains of sand left from a bucket of soil, looking

down to find a golden fortune in the dish.

Panning

works well when a gold seeker is just prospecting, looking for a good place to

work, but successful diggers need to process as much dirt as they can and then

‘save’ as much gold as possible. The prospector’s pan was

(and is) like a frying-pan, 16 inches (40 cm) across, with sides sloping down

to a base, 10 inches (25 cm) across. It was 3 to 4 inches (8–10 cm) high,

giving a side with a 40–50° slope. The angle was not all that critical, as long

as it was steep enough to hold the gold in and low enough to let the mud and

sand wash away.

Gold pan, Sovereign Hill, Victoria.

The prospecting

pan is too slow to use on its own, but it was often used as a last step

after the cradle, with the pan being used to clear the gold of the last bits of

rock and soil. The idea is always to

separate gold from soil, dirt or sand, getting rid of the waste as

quickly as possible, but not if it means losing any of the gold. A skilled lone

gold panner can ‘clear’ a bucket of sediment in about ten minutes, which means

washing less than a cubic metre of soil in a long day. This was not enough,

said Francis Lancelott in Australia As It Is:

Only

those who from poverty or eccentricity work single-handed use the pan. It is

better to work in parties of four to eight and wash the soil in a cradle.

Nobody

seems to have published figures that would let us compare the pan against the

cradle, but the cradle was always seen as better. As you might expect from the

name, the it resembles a traditional child’s swing cot. It was a suspended

wooden box with an iron grating, which held stones on the top level so they

could be checked and removed.

The

smaller fragments including the gold fell through the grating. A flow of water

washed away the sand and mud, while the gold was trapped with some of the

dross, on the lower level. There were a number of variants on the cradle and a

few people used a hairy surface to catch fine flakes of gold, but slats or

grooves were more common.

Georgius

Agricola offered this picture of a sort of 16th century cradle.

In

ancient times, Jason and his Argonauts were really just looking, not for a

Golden Fleece, but for rams’ fleeces that had been left in a gold-bearing

stream, somewhere around the Black Sea. This was something everybody had known,

at least since Agricola explained it in a book on mining published in 1556, the

same one that featured his version of the cradle. He said:

The

Colchians placed the skins of animals in the pools of springs ; and since many

particles of gold had clung to them when they were removed, the poets invented

the “golden fleece” of the Colchians.

By

the 1850s, cradle designs were far better. Gold hunters wanted to change dirt

to mud, pick out the rocks and either break them up if they contained gold or

throw them to one side, and wash the rest down the slope where bars, riffles,

or sometimes, grooves full of mercury, caught the gold. The small stuff fell

through to the lower level, where water was supplied, usually by a dipper

operated with one hand, while the other hand rocked the cradle.

At

least one cradle had come to Australia at a surprisingly early date, going on

an advertisement that appeared in the Sydney press on 17 May, 1851, just as the

gold excitement began to bite:

Notice.—Whereas

a

Gold Washing Machine, ex-Artemisia, from San Francisco, California, is

now lying unclaimed at the Stores of the undersigned: Notice is therefore

hereby given, that unless the claims on said Gold Washing Machine be settled,

and all expenses incurred be paid, on or before the 24th instant, said Gold

Washing Machine will be sold, for account of whom it may concern. MONTEFIORE,

GRAHAM, AND CO. May 16.

One

of those people who had been to California was Edward Hammond Hargraves. He and

a friend knew all about the shepherd Hugh M’Gregor and his gold, and the Big

Hill nugget. Hargraves had also heard about how the Californian gold rush had

started. He understood how to get a rush going, and it wasn’t about finding

gold: it was about persuading people.

When

a few nuggets were found on the American River in California, an old miner had made

James Marshall a cradle to separate gold from dirt. This was the original

cradle, and he showed other people how to make and use it. Some months later, a

merchant named Sam Brannan bought up all the equipment that gold seekers would

need. Then he rode through the streets of San Francisco waving a bottle full of

gold (which he had bought) shouting, “Gold! Gold from the American River!” The

rush began and Brannan made a fortune selling the needed equipment.

Hargraves,

who was celebrated as a hero for ‘finding’ gold, probably imagined himself like

this.

If we know nothing about him now, people

certainly knew about M’Gregor’s gold well before Hargraves announced his great

goldfield. In June, 1850, The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser said there was no doubt that

a shepherd, ‘old M’Gregor’, had been getting gold at Mitchell’s Creek in the

Wellington Valley, and that he was probably still doing so.

Simpson Davison went to California with

Edward Hargraves in 1849.

Before he left, Davison had learned from a shepherd named Thomas Appleby how

and where M’Gregor found his gold. Davison said later that M’Gregor’s ‘secret’

was probably known to many shepherds. This knowledge could have started a gold

rush, but it didn’t.

Then

in 1851, Hargraves announced finding a huge goldfield, stretching all the way

from the Wellington Valley to the foot of the Big Hill, an area far too large

for the authorities to stop a rush, and it ran from M’Gregor’s gold grounds to

where that unnamed road gang convict found a nugget in 1824. Hargraves did not

discover either of those, so what did he really

do?

Basically,

he pulled off a very clever stunt, but what did he not do? We know now that Hargraves did not find the first gold in

Australia, in fact he found no gold at all, and he was not the first to say

from experience that there was gold in Australia. He seems not to have even

seen any Australian gold until his assistants found some for him, early in

1851.

Many

competent geologists knew there was gold in Australia. They even said so, but

still there was no gold rush here. Hargraves knew where the gold was because

others (like Hugh M’Gregor and that convict on the Big Hill) had found it.

Hargraves knew that people coming back from California understood how to use a

cradle to find gold.

Hargraves’ co-conspirator, Enoch Rudder, in old age.

So

the trick was to get those knowledgeable and experienced people excited, and then to stop the government from

blocking a gold rush, as they had done in Victoria. If enough people got out

there over a wide enough front, the government would never stop the rush.

Hargraves

wanted the credit

and any rewards for ‘finding’ gold. He

wrote a letter to the colonial secretary in April 1851 about his ‘discovery’ of

gold between Wellington Valley and the Big Hill but, on the same day, his

friend Enoch Rudder wrote to the newspapers declaring that Hargraves had found

a large goldfield.

Now

everybody knew there was gold to be found, and a few people set off for

Bathurst, hunting for gold, and the area covered in Hargraves’ letter was too

large for the government to step in. By early May, the first gold hunters (probably

people who had been to California and returned) reported finding gold, and the

rush began. By mid-May, Sydney’s merchants were clamouring to sell diggers

everything they needed.

Like

Brannan, the Californian merchant, they knew an easy way to get rich from gold.

In Melbourne, the government was worried about losing workers to New South

Wales, and now they needed gold to be found, south of the Murray River.

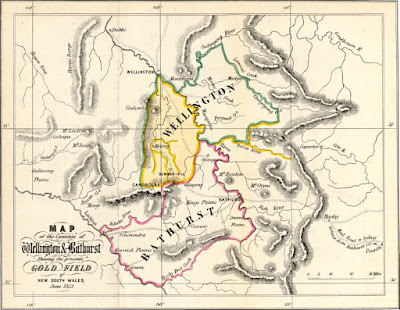

Diggers rushed to buy this 1851 map of the ‘Gold Field’. (It includes the Turon.)

Melbourne

sent a scientist to look for gold in the Pyrenees Ranges, in the central

highlands of Victoria, and soon there were goldfields everywhere. In those

days, news spread slowly: a very fast ship might make a one-way trip between

Australia and Europe in three months, but four was more usual, and six months

was not uncommon. So people in England first heard about the Australian gold

rushes in The Times on 2 September 1851. The excitement began.

|

William

Strutt, Off to the diggings. S. T. Gill (probably), people reaching the

diggings.

Globetrotters

People rushed to the Australian goldfields from almost every land on Earth.

There are accounts of life on the goldfields from Poles, Americans, Hungarians,

Danes, Germans, Italians and Frenchmen, and they all mention seeing people from

a multitude of nations, ranging from China to India, New Zealand, Scotland and

Africa.

Digging for gold

Most of the gold was under the soil in

placer deposits which are old, buried creek beds, and they had to dig down to

get them. When all the alluvial gold has been gathered, people start poking

around the rocks upstream, looking for more gold, but gold rushes usually began

with people finding alluvial gold and then gravity-sorted placer deposits.

These involve gold or other heavy minerals, usually formed in and by creeks, streams

and rivers.

Rocks change slowly under wind, rain, frost

and the effects of air. First, the rocks weather, as some of the minerals break

down, then erosion carries the pieces down under the force of gravity. The

deposits form when gold fragments are left in streams, gathered in places where

the current is strong enough to wash away the silt and sand, leaving small

clumps and collections of gold behind. The high density of the metal keeps even

the tiniest gold flakes and grains on the bottoms of fast streams that can wash

away ordinary sand and rock.

It all comes down to gravity and the action

of water or wind. To be concentrated by gravity, a mineral needs to be more

dense than what is around it, and if it is to last, it needs to be able to

stand up against chemical attacks. There is a giant book of world history lying

in the rocks beneath the scenery, and while luck always plays a part, the

successful gold hunter will be the one who can read and deduce an area’s

history from limited clues, and predict the best places to look.

Where a stream meanders, it sometimes

escapes from its bed, leaving an old channel with its load of gold to be filled

in and covered over by silt, dust, volcanic ash or even a flow of lava.

Sometimes massive forces lift the land up so the stream stops flowing, and a

similar burial happens.

Once it has been covered, the gold lies

there waiting to be found by somebody willing to dig hopefully. The gold has

been concentrated enough to make it worth taking from the ground, but how do

you find where it is hiding? What raises the hopes enough to inspire hard work?

Digging for gold in hard rock is a bit silly

until you know there is gold in the area, and alluvial gold told people where

the metal might be found in nearby

rocks. Then people needed to look around for the right rock types, the source

rocks that gold had been found in before.

Digging

deep for gold

The first people on a goldfield took the

easy gold in the gravel of the creeks, but more gold was hidden in the soft

clay beneath the gravel. This sort of mining was called ‘surfacing’, but as the

surface gold ran out, the chasers after gold had to change their methods. They

dug shafts down into the top layers of a light but variably coloured soft shale

called ‘the pipeclay’.

Everybody has heard tales of miners going

down shafts to avoid ‘the traps’, the troopers who came around checking for

licences, but what made diggers start digging deep holes? Most of the gold

seekers were practical people, operating on a limited budget, and once their

money ran out, they would have to sell up their equipment and go home. They

were unlikely to risk their money in sinking a shaft, just on chance. So what

sort of hopes, what knowledge did they have?

During the 1850s, many of the shafts went as

deep as 200 feet (call it 60 metres) straight down. The first shafts were

driven down through sediment—sand, soil, small rocks and clay, not through

solid rock, though later on, shafts would also be cut through rock. Soil was

easier to dig than rock, but it was still hard work. When they cut down through

sediment, their shafts needed ‘timbering’ or ‘slabbing’. That meant cutting and

adding timber frames to stop the sides collapsing, and there was also 200 tons

of earth or more to be removed from the hole.

If gold turned up at the bottom, everybody

was happy at their good fortune, but if the hole missed running into gold, the

party had wasted a small fortune in sinking and reinforcing the long shaft. The

account that follows relies heavily on William Westgarth’s Victoria and the Australian Gold Mines in 1857.

At first, diggers washed everything, until

people noticed that some patches were richer than others. Westgarth explained

it well: ‘Large nuggets were unexpectedly reached, both near the surface and

deep below it. No rule could ever be established as to these ‘princely

visitors.’ Then somebody noticed that where the gravel came in contact with the

shale, there were pockets that were full of gold.

The cleverer miners began to work out a few

principles. When ‘veins’ of gold particles turned up in the clay, there was

likely to be more gold nearby, and traces of rust in the quartz sometimes

indicated gold in the area as well. Diggers explored more widely when they

found such signs.

In the 1850s, there were people who called

themselves geologists, and ordinary folk could buy books on geology, but nobody

had too much of an idea about what lay beneath the scenery. Geology was still

an infant science.

Glaciers were sort-of explainable, but volcanoes

were poorly understood and earthquakes were a total mystery. There was no real

idea of such a thing as geological history, and that made the rocks harder to

understand.

Ordinary people had no idea that far below

the ground they walked around on, there were old land surfaces and creek beds,

ancient country, buried beneath deep layers of sediment. So nobody thought

there would be much point in ‘bottoming’’ the pipeclay, digging through it,

because the pipeclay seemed to go down forever.

When somebody drove the first hole through

the pipeclay, they must have got lucky. Just a few bad holes might have

discouraged anybody else from trying, but clearly, some of the early trial

holes made their diggers a fortune.

By that good luck, a pattern was set.

Looking back with modern knowledge, we can see that the first lucky burrowers must

have dug blindly down into an old and buried creek bed, still with the load of

gold it held when it was first covered over.

When the shaft-sinkers began to find

gold-bearing ‘drift beds’ they learned to trace ‘leads’ through the drift bed

until they struck a ‘gutter’—an old creek bed. Geology was advancing fast, and

by 1857, educated observers like Westgarth understood what the miners had

found:

The gutter may have been a continuous

feature in the past when it rolled its golden washings through the valleys of

the ancient surface; but as it did not leave in its channel a continuous

indication of gold, so the lead was constantly being lost by the eager miners,

who, in the pursuit, were compelled to sink here and there new shafts of one or

two hundred feet in depth.

Puddling and crushing

A lot of gold-bearing dirt came as clay

lumps that get trapped in the top of the cradle and washed away with the

gravel, still holding their gold. The clay needed to be ‘puddled’ in a tub,

turning it into mud and silt with flecks of gold that could be collected by the

cradle.

Puddling in a tub.

Later, horses were brought in to do the hard

work of operating puddling machines, and soon there were thousands of them, all

over the goldfields. They commonly used a lot of water and generated a lot of

muddy sludge, but the diggers who used them did well—unlike the rivers.

The gold found in streams or soil was once

inside rocks. Gold buried in the ground was also once inside rocks, like the

gold the dredgers got. Sometimes, the gold is still in the rocks, and the only

easy way to get it is to grind the rock to powder, so the rock can be separated

from the gold.

Crushing ore is an ancient practice, going

on a Bronze Age gold mine that was found in Kazakhstan in 1937. The mine had

fallen in, some thousands of years ago, and the fall trapped two miners, and

preserved their mainly stone and bone tools, though there was also a bronze

chisel. Not far off, there was a primitive ore-crushing plant, made of stone

slabs. Nearby, there were hammers.

The crushing technology either survived, or

it was reinvented. Georgius Agricola showed an illustration of a crushing

machine in the mid-1500s, so we know they have been around for at least 300

years. Most of the early machines were water-powered like Agricola’s model,

though some were animal-powered.

Originally, the idea of crushing was to

break the rock and gold into small pieces, so the fragments could be separated

into gold and anything else. Later, crushing was used to let quicksilver,

cyanide or chloride of lime come in contact with the gold to dissolve it out.

The early alluvial miners didn’t need these methods, but once people started

hard-rock mining, crushing in some form became essential.

Some form crushing methods were quite

primitive. In 1854, Claus Gronn met four men who used hammers and chisels to

chip a hole, twelve feet square and ten feet down, in a quartz seam. These

primitive hard rock miners collected quartz lumps all week.

On Saturday, they crushed the lumps,

roasting the quartz on an iron plate, pouring cold water on the quartz to make

it crack into smaller pieces that could be hammered into ‘sand’. After that,

they washed the ‘sand’ in the usual way.

Most people preferred stampers. Australian

stampers were usually driven by horses or steam, though in August 1853, J W

Cochrane told Scientific American he

was taking orders from Australia for his quartz gold crusher, a device which

used cast iron balls rather than stamping hammers to reduce the rock to grains.

Steam had started to take over by 1848, when

Scientific American described a

steam-powered gold machine. It used two 45 horsepower

engines to drive hammers that pulverised gold ore before a stream of water

carried the powder over a table covered in skin, hairy side up. Later, the gold

was recovered from where it had settled among the hairs.

|

Cochrane’s 1853 quartz crusher(left) and an

1859 American stamper, driven by steam (right). These are on different scales.

There was some resistance to steam. In 1855,

The Argus reported admiringly on a

model of a new quartz stamping machine, arranged by Mr John Phillips, an

engineer and surveyor from Cornwall (we met him earlier as the finder of more

gold in South Australia). Now living in Castlemaine, Phillips favoured horses

over steam, because, he explained, any miner could manage horses.

The twelve hardwood stampers each weighed

two hundredweight (about 100 kg), and each dropped six times a minute,

delivering a total of 72 blows a minute. The machine was easily taken apart and

loaded onto a dray, and anyone with basic skills in carpentry and blacksmithing

could repair it, said Phillips.

In

the long run, steam won out. In March 1860, The

Age reported that there were 581 steam engines on the goldfields,

along with 3982 horse-powered puddling machines. Still, Beechworth used mainly

water power and sluices while Maryborough had a windmill-powered quartz crusher. The

figures varied a bit from source to source, but the picture stays the same. In

1861, Scientific American reported

that Australia had 294 steam engines of the aggregate power of 4137 horses;

also 3957 horse puddling machines, 354 horse gins, and 128 water wheels, in

alluvial workings. The magazine also mentioned another 420 smaller steam

engines, equal to 6696 horse-power.

That was a total of 714 steam engines with

10 833 horsepower. Countless horses would also have been engaged in hauling in

the firewood for the steam engines. The goldfields also had 6 water wheels, 40

horse-powered crushers—and 184 horse gins used in quartz mining and crushing. Within

just a few years, the romance of the gold rush had gone—but for most people on

the goldfields, there never was any

romance. Gold-seeking was about getting rich, and only poets saw any romance in

that! To everybody else, it was hard work and cunning science.

Finding

a place to dig

A small tributary to the Turon River offers tell-tale signs of washing.

When somebody washes for gold, muddy water

flows downstream. If the clear water of a small creek suddenly went muddy, the

wise miner wandered upstream, to see where the mud was coming from, and pegged

a claim near there.

Having reached a goldfield, the next

challenge was choosing where to dig. Seweryn Korzelinski saw four Irishmen

living in two tattered tents. He saw that these men spent two days a week

digging and the rest of the time drinking and fighting. A three-pint bottle of

brandy cost £1, so he guessed they were getting gold. He sank a shaft close to

their claim and it paid off.

Over time, word would spread, and people

would arrive. A clergyman named (we think) Morison told of two men finding gold

near what he called an ‘accommodation house’ in a district where there were no

more than a dozen adults within 60 miles. The news soon spread abroad, and within three weeks there were about 1500 people

collected within a half-mile length along the creek, near where just two men

had been working. The secret of a strike never lasted, and Charles Rudston Read offers a tale

of a Bendigo Creek man who discovered gold. He and his men started to collect

the gold, but he told the secret to his wife, who told it confidentially to a

neighbour’s wife, who only told one other, and so it went, each only sharing

the story with one other. Then followed the normal—and inevitable—gold rush.

A mixed bag of ups and downs

Like

the curate’s egg, a gold rush is good in parts. Californian and Australian gold

fed the revolution in science and technology of the 1850s, but not everything went

as well. More people crowded into cities where disease ran riot, and others

were coerced to work where they did not wish to be. Overall, humanity probably

gained, but there were definitely costs to be borne.

The

Eureka Stockade

There had been successful revolutions in America and France

in the later 1700s and, by the 1840s and 1850s, more people could read, paper

was cheaper, printing was faster, and steam transport enabled ideas to spread

more quickly. Soon, telegraph wires would link nations and ideas would spread

even faster. The desire for change was in the air and Karl Marx called it a

stalking spectre.

Europe had seen a number of failed revolutions in 1848,

and refugees from the losing sides in those battles had scattered, some of them

reaching the goldfields of Australia. The Victorian colonial government knew

about these revolutions, and Victorian Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe

feared what he called the ‘red republicans’.

It would have been wiser to avoid repression, but the

squatters wanted the diggers back working on their farms for low wages. To make

this happen, they demanded an increase in the fee for the miner’s licence that

everyone on the goldfields had to have—even storekeepers and blacksmiths. In

June 1852, La Trobe doubled the licence fee from 30 shillings a month to £3 a

month, arguing that it had to go up because of an increase in the cost of

administration, but because people were refusing to pay for their licences, the

police were sent on ‘digger hunts’. They often robbed their prisoners, and new arrivals

were arrested as they reached the fields, before they could even obtain a

licence.

When a drunken Scot called James Scobie offended

publican James Bentley on 7 October 1854, Bentley and his henchmen chased the Scotsman

and beat him to death, after which a (most probably) corrupt magistrate let

Bentley off. On 17 October, a crowd of about 10,000 miners gathered and, in the

presence of troopers and a goldfields’ commissioner named Robert Rede, they

burned down Bentley’s Eureka Hotel. Bentley had already fled.

On 18 November, Bentley and two accomplices were

sentenced to three years of ‘hard labour on the roads’ for Scobie’s death. This

might have helped settle things down, but Charles Hotham, who had replaced La

Trobe as lieutenant-governor, wanted the ringleaders who burnt down the hotel

arrested, and some of them were.

There were more digger hunts, and John D’Ewes, the

corrupt magistrate, was dismissed. Then armed troops were sent in. The diggers

stopped one group of troops and tipped their carts over. The troops’ drummer

boy, John Egan, was shot in the leg. In the commissioner’s camp, soldiers

believed Egan was dead, so the army was out, looking for revenge.

The authorities were alarmed by the demands of the

diggers’ Ballarat Reform League. The League wanted things that we now take for

granted, such as everyone having the right to vote but, in 1854, that was

regarded as a dangerous notion.

The Chartists

This British democratic movement frightened the Establishment, the Bosses,

and rightly so, because the Chartists cared about merit, not any sort of

birthright. Their ‘six points’ were: *votes

for all (provided the ‘all’ were male, white and adult); *constituencies of equal size; *paid members of parliament; *secret ballot; *abolition of the property qualification and *annual elections. The first five points are all taken for granted

now—or surpassed, in the case of the right to vote.

On 30 November

1854, Commissioner Rede sent troops out to check licences, but the people had

voted not to show their licences, and the troopers were jeered at and stoned. Some

arrests were made, but more diggers gathered, the Eureka flag appeared and,

beneath it, the diggers swore to uphold their rights and liberties. They

started erecting a stockade—a small wooden fort.

On Sunday 3

December, thinking there would be no attack on the holy Sabbath, many of those

in the stockade drifted away. At 3 am, the troops moved in and, when a shot was

heard, their commander, Captain Thomas, shouted: ‘The Queen’s troops have been

fired upon. Fire!’

Six troopers

and 22 diggers died, and several of those people were deliberately murdered,

perhaps as revenge for the drummer boy, while another 12 diggers were wounded. Out

of 120 prisoners, 13 were charged with high treason, but all were found not

guilty. A few years later, Victoria was a democratic colony, and two of the

Eureka Stockade leaders had become members of parliament. The gold diggers had

won in the end, and democracy was oozing out.

Immigration and gold

Between

the start of 1842 and the end of 1851, immigrants and immigration were the

subject of numerous articles in Australian newspapers. Sydney stopped receiving

convicts in 1840—although one more convict ship, the Hashemy, arrived in

1849 amid great protests by people against transportation. While other colonies

were still getting fresh convict labour, squatters in New South Wales knew that

the supply of cheap labour was drying up.

People

tried bringing in ‘coolies’—indentured labourers from China and India who were

contracted to work for an employer. In South Australia, some settlers imported

indentured workers from Germany, but this did not work particularly well. Indentured

workers were poorly paid, and treated worse.

Attracting migrants

With

the lure of gold drawing labour away, some of the squatters wanted to bring

back the convict system, but the anti-transportation people had the upper hand.

The only solution was to get more immigrants to come to Australia, mainly from

Britain. Australia was competing with America and Canada, which were closer to

Britain, so the ocean voyage for immigrants was cheaper and shorter.

That

said, if people were going to travel all the way to Australia, they could also

go on to New Zealand, which had a cooler climate. There were no good reasons

for people leaving Europe to come to hot, dry, dusty Australia, and farmers,

like other employers, needed an over-supply of immigrant workers to keep the

wages bill down, and profits up.

Streets lined with gold?

In an article in his newspaper, Empire,

Henry Parkes welcomed the discovery of gold in Australia as a way of stopping

the transportation of convicts. He argued that the politicians in London would

not want to send burglars and highwaymen to a land full of gold!

This

helps to explain the glee with which the start of the gold rush in Australia

was greeted. The hope of many colonists was that people would come to dig for

gold, and either do well and buy a farm here, or do poorly and settle in

Australia to work as labourers. They were right.

Australia

benefited from the misfortunes of poorly prepared gold hunters, who found very

little gold, while paying high prices for everything on the goldfields. People

who had had a bad experience during their voyage to Australia were often

tempted to settle, rather than risk another sea voyage. Between 1851 and 1860,

more than 600,000 people reached Australia, with most of them ending up in

Victoria.

Some

of the gold diggers kept on mining, working underground in the hard-rock mines

that replaced alluvial mining. By the time that sort of gold began to run out,

many of them were too used to living in Australia to ever want to go back home.

The

cities and towns which had been briefly drained of their populations during the

gold rushes grew even larger than would have been dreamed of in 1851—and the

colonies were also far more democratic, because Australia had the highest

quality of life of any nation and, in prosperous times, nobody minded giving

the vote to more citizens.

Thanks to the gold rushes, Australia would never be the same again.

Sluicing and dredging

In the 19th century, miners in California,

Australia and New Zealand often made races, channels that went around hillsides

and filled dams to provide water to wash for gold. Then somebody in California

got the idea of using a race to feed water into a vertical pipe so it came out

of a nozzle at the bottom of the pipe under pressure.

There were similarities and differences

between the Californian operation, and that at Las Medulas in Spain, almost

2000 years back. Both used water on a large scale, but the Romans collapsed the

mountain from inside, leaving a lot of the mountain standing, while sluicing,

or ‘hydraulicking’, washed everything away.

People had used barrows and carts to carry

‘dirt’ to where it could be washed. Now, in California, hydraulicking did the

whole lot in one go. They just had to wash the mud into a channel that worked

like a giant cradle and wait for the gold to collect. It was like shooting fish

in a barrel.

Real fish were certainly killed downstream:

they choked to death, their gills clogged with mud, or sludge, as it was often

called. The

dead fish were a minor problem, because not many people ate the fish. Besides,

fish can’t complain and fish can’t vote. On the other hand, farmers can

complain, farmers can vote—and farmers can sue.

This nozzle was called a monitor. Oriental Claims, Omeo, Victoria.

In California, the Sacramento River silted

up and water flooded farmers’ fields. The silt also stopped steamers carrying

freight and passengers on the river, so the farmers got angry, and went to

court in the 1880s. That was the first ever environmental lawsuit, and it

stopped most hydraulicking in California.

In Australia, hydraulicking continued, but

Australian miners were made to control the sludge. Their work gave us the

spectacular 30-metre (10-storey) cliffs on the Oriental Claims goldfield near

Omeo in Victoria. There were many complaints and official enquiries and late in

the 19th century, Victoria had a special Sludge Commission, but it was more

concerned with the sludge problems from dredging, which happened mainly in the

late 1800s and early 1900s. The Oriental Claims operation also created cliffs

that would continue to erode.

Damage after hydraulicking: Oriental Claims,

Victoria.

Dredging works because a river valley

changes, and over time, the river winds and cuts new beds through the valley floor.

As it shifts, it leaves deposits of gravel, sand and mud behind. In gold areas,

gold will lie in pockets across the valley floor in old river beds, perhaps not

enough gold for cradling or panning, but big-scale mining can still pay off.

A dredge can work its way along the river,

digging up everything on one bank, extracting the gold and dumping the waste

gravel on the other side, but dumping the clay and mud in the river. Bit by

bit, the river gets moved across the valley, leaving a gravel wasteland behind.

The mud and silt wash down, perhaps all the way to the sea, but often forming

huge mud banks, clogging the river downstream, making it flow out, over its

banks, carrying some of the silt with it.

Labour shortages

On the road and at the diggings, people

rode, walked, camped or worked with, “… merchants and cabmen, magistrates and

convicts, lawyers and their clerks, physicians and scavengers, fashionable

hairdressers and tailors, cooks and coachmen, aldermen, constables, colliers,

cobblers, sailors, shorthand writers, and quarrymen”, said the Religious Tract

Society.

According to Manning Clark, in his 1979 A History of Australia (volume IV), a

gentleman squatter offered a returned (and successful) digger a shilling if he

would lift a bag of sugar off a dray. The digger responded by putting his foot

on a stump. He invited the squatter to tie his shoelace, offering to pay five

shillings for the task. This story either began as a Punch cartoon, or soon became one. Whichever way the story began,

the people who knew how wealthy diggers behaved accepted the tale as true.

The madness that infected people and sent

them rushing off after gold still influenced the successful diggers who, in

many cases, spent all they had won on a giant spree, and then had to choose

between returning to digging again, or going home with nothing.

George Butler Earp had an even better story

than Clark’s shoelace tale. Earp seems to have been an English lawyer, but he

became a merchant in New Zealand in the early 1840s. Back in England, Earp

turned his hand to writing naval history, but arising from his Australian

experience, he wrote The Gold Colonies of

Australia, and that is where we find his tale.

A grazier visited his former shepherds at

the goldfields, offering them high wages to come back and shear his sheep. They

said they would only do it if he would give them all the wool, and then, as he

was stalking off in a rage, they called him back, to offer him 15 shillings a

day to be their cook, but the shortages of workers were no laughing matter. In

the Victorian town of Portland, things were dire, according to a Launceston

paper, The Cornwall Chronicle on 21 February

1852, that quoted an earlier issue of the Portland Guardian:

… three

blacksmiths out of five have left for the diggings, the rest are to follow;

only one wheelwright is left; the brickmakers have not left one of their trade;

out of three medical gents, one only is spared to us; of three public school

masters two are on the road to the diggings; tailors have sped their way to the

diggings; our tin-plate workers are gone to the diggings; printers are leaving

for the diggings; woolsorters have left for the diggings; the brewer is off to

the diggings …

— The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston), Saturday

21 February 1852, 114.

Faced with the reality of a gold rush, the

colonial governments worried about workers going to the diggings. They advised

farmers: stay on the farm and don’t risk an unprofitable trip to the diggings,

‘… and each wheat paddock will be found to turn out a little Ophir of itself’.

Farmers might have listened to that advice, but poorly paid farm labourers and

shepherds would not hang around, and they weren’t alone.

The sailors were off and running as well—and

at least one captain also joined in. Because sailors would want to desert,

ships avoided Australia. This made it hard for passengers and imports to

arrive, and even harder for gold and exports to leave, so special

discouragements were arranged for absconding seamen.

George Wathen reported this sight that

greeted sailors as their ship reached Melbourne: ‘… a great white hulk, with

“REFRACTORY SEAMEN” painted in large capitals on her side, is calculated to

arrest the attention of newly arrived sailors who may be meditating an escape

to the gold-fields.’

This was the Deborah, which was bought by the Government to make a floating

prison for seamen who had deserted. The hulk was anchored close inshore by the

Williamstown lighthouse, and yellow buoys were laid down to mark an area where

boats were banned. Sentries with loaded muskets were ordered to challenge all

boats entering the zone, and to fire on those who did not answer

satisfactorily.

On 30 June, 1853, the ship held 91

prisoners. By 31 December in that year, the number was 161. By the end of

April, 1855, the hulk had been empty for some time, and it stayed empty. The

gold rush was still going on, but the mad rush was over.

Goldfields

daily life

There was money to be made, drawing and painting goldfield

life for lucky diggers to buy, and at an age when photography was just starting

to edge out miniature portrait painting, this was a quick money maker for

artists like S. T. Gill. Gold might be found by panning and cradling surface

soil, by deep sinking (digging a shaft), puddling and cradling, and Gill showed

all of these.

S. T. Gill, surfacing and deep sinking.

S. T. Gill: a prospector panning, two men puddling, and

cradling.

With no digging on a Sunday, a few diggers might attend a

church service. Most would be at the ‘coffee tent’, which sold sly grog.

Sheep and cattle were driven from NSW for sale and slaughter

on the Victorian goldfields, the only way of ensuring fresh meat before

refrigeration or ice became available.

Henry Hopwood set up a £1500 punt near the junction of

the Murray and the Campaspe rivers, just downriver from Echuca. With a couple

of hundred metres of fence, Hopwood turned a large tongue of land between the

rivers into a huge holding paddock. Punts were cheap, but slow, and even if bridges

looked more attractive, the bridges could wait.

William Strutt saw the effects on city society when all the men went away, digging for gold. There was a blurring of what should or not be done by women.

Diggers’ tents, exterior; and Eugene von Guerard’s sketch of the interior of a fancy one, complete with fireplace (a larger view appears in chapter 9); George French Angas’ view of washing for gold; and a gold buyer.

After the gold rushes, Australia had to change.

Golden

villains

This section draws on my book Not Your Usual Gold Stories, where you will find more detailed

versions of these stories.

From James Daly’s fake nugget and alleged ‘gold mine’ near

Sydney’s South Head, there were tricks and ploys galore. Hargraves’ combination

of the 1824 Big Hill nugget and Hugh M’Gregor’s finds in the Wellington Valley,

to claim there was a gold field “…from the foot of the Big Hill to a

considerable distance below Wellington, on the Macquarie…” was less than totally

honest, but it set the gold rushes running, and opened the way for many real

villains.

Francis Lancelott claimed the title of ‘Mineralogical

Surveyor in the Colonies’ or ‘Mineralogical Surveyor to the Colonies’. At least

three colonies had official mineralogical surveyors, but Mr Lancelott was not

one of them. He had possibly spent some time in Australia, or stolen his

information from people who had been in Australia. I rather suspect the latter,

as the single mention of him in Australian newspapers is a brief mention of his

book, Australia As It Is.

The only other trace of Lancelott may be as the author

of The Queens of England and Their Times,

published in two volumes in the late 1850s, and The Pilgrim Fathers. Somebody of that name wrote a number of songs,

but he wrote no other works on Australia or on minerals. At least some of his

biology was lifted from articles written in the 1820s by judge Barron Field.

Would-be gold seekers, travelling on ships from Europe,

Canada or America, could read ‘guides’ put out by hacks who had never even been

to sea, let alone to the diggings in Australia. These pamphlets were cobbled

together from books, advertisements, letters, news reports, or anything else

which seemed to be about gold. When they could get no information, writers

often just made their facts up, and the only mining ‘John Sherer’ ever did

seems to have been in other authors’ works to write of his time in Australia.

Now consider this map:

Captain Vetch’s plan for Australia.

Many Englishmen of a certain kind liked telling people how

to behave in Australia, even though they had never been there. While he was in

gaol, Edward Gibbon Wakefield drew up his plans for a convict-free settlement

in South Australia, and Captain Vetch of the Royal Engineers looked at the

colonial map in 1838 and decided the boundaries were wrong. He told the Royal

Geographical Society that the foolish Australians needed more straight lines on

their maps, with nice, square chunks of land and a nice network of roads

running uselessly to useless places.

Vetch was just a bit silly, and not really a villain,

though after 1851, gold claims emerged just as fast as cryptocurrency scams do

today. John Calvert, for example, was

a complete fraud. He first came to notice in Sydney when he placed a

curious advertisement in October 1851:

RICH GOLD DISCOVERY. Mr. CALVERT, in his Geological Survey of

the colony, has discovered a Rich Gold Deposit near the locality of Bathurst,

which would afford ample and lucrative employment for a Company ; but which his

own engagements prevent him from availing himself of, otherwise than by

disposing of his information on the subject, for which he will not accept less

than One Thousand Pounds. None but capitalists need apply.

The colonial response was a combination of snigger, sneer,

and hearty guffaw, and the contempt continued. It shows best in a letter Edward

Hargraves wrote to the Sydney Morning

Herald in September of 1853. This described various evasions that Calvert

had used, and noted that Calvert had appeared out of the blue only after his,

Hargraves’, announcement. He added that Calvert’s original story must have come

from the pages of the popular comic magazine, Punch. Then Hargraves delivered a killer blow:

… he has certainly turned to good account the two cwt. of

quartz he bought from Mr. Hale, the goldsmith, in George-street, for forty

shillings, and at the time of purchase said he would astonish the natives with

it on his arrival in England.

On the other side of the world, Calvert was largely safe

from the slings and arrows of the Australians who knew him as the man who had

taken ten shillings a day from the good folk of Queanbeyan to find gold—and had

then failed to do so. In 1890, a gentleman in South Australia recalled Calvert

as a young man of 21 sailing to Australia on the same ship in 1843: Calvert was

regarded even then as ‘the “Baron Munchausen” of the ship’.

John Calvert: liar and/or minor crook.

This was when, thinking himself the last man standing,

Calvert returned to Australia to offer a series of Boys’-Own tales of his adventures. For example, he claimed that he

walked with Aborigines as far as the 20th parallel, roughly to the Tanami

Desert, and this happened in 1843. The tale is unbelievable, because much of

Australia was in drought in that year, so they would have died.

On another journey around 1847, he said he set off into

the W. A. desert with eight men and discovered “a mountain of gold”. He had no

witnesses, because all of the other men perished of thirst before he alone was

saved by a rainstorm. After that, he explained, a helpful Aborigine took him

back to his waiting ship, Scout,

which he had commissioned and built in 1847. This, he said at first, was a

yacht, though he later called it a brigantine.

The vessel’s form could easily change, as it never

existed. There were just two vessels named Scout

in or near Australian waters in 1847. One was a Royal Navy sloop in the

vicinity of Amoy (China), the other was J. T. Waterhouse’s clipper brig, which

often visited Australia. The voyages of Waterhouse’s Scout are all laid down in the Shipping Intelligence columns of the

colonial newspapers, and there is no gap when that vessel could have been

chartered to Calvert.

Calvert’s Scout

seems to be based on the yacht Wanderer,

a genuine schooner belonging to another dodgy character, Ben Boyd. The

difference between the two vessels is that Wanderer

can be tracked in the Shipping Intelligence columns, just as easily as

Waterhouse’s Scout. The records show no

other vessel called Scout calling at

Australian ports in the 1840s, but back in the 1890s, when Calvert was spinning

his yarns, that sort of claim was a whole lot harder to test.

Wildman’s Gold

In 1862, Wildman (he appears to have been called Henry) was

convicted for burglary, perhaps at Heanor Hall in Derbyshire. His nationality

has been variously given as Dutch, German or ‘foreign’). Arriving in Lord Dalhousie in 1863, he was serving

an 18-year sentence in Perth, but he wanted out. In late December 1863, he

claimed that he had found gold near the Glenelg River) seven years before. He

said he had been the chief mate of the ship Maria

Augusta, sailing from Rotterdam to Java, and when the ship lost her rudder,

the captain had put into a bay on the north-west coast of Australia, so the

sailors could cut timber to replace the rudder.

According to Wildman, while the ship was anchored in

this bay for 12 days, he picked up 8 pounds of gold nuggets in 2½ hours. He

said he sold these to a Mr Johnston, a bullion merchant, in Liverpool, for £416

in September 1856. He later amended the buyer’s name to Samuel Jones of ‘…

Waterloo Road; Liverpool, near DaCosta’s shipping office’, rather than

Johnston. Pressed for more information, Wildman pointed to a position on a map,

and said the gold was collected ‘some way up’ a river. This was an area that

Sir George Grey had said in his journal might yield gold. Explorers, even good

ones (and Grey wasn’t), often expressed hopes like that, and Wildman, as a

forger had to be literate, so he may well have read Grey’s journal, or have

heard of Grey’s comment.

He offered to take people there to locate the gold, in

return for a free pardon. He explained that he had left some papers with his

wife, and while he had no documents or maps with him, he knew the place, and

had always planned to charter a vessel to go back for more gold. He would not

reveal the exact location at first, but he said the longitude was less than 129

degrees East.

The best scams are based on a few facts that can be checked,

with false details tacked on. Perhaps some foreigner, known to Wildman, had

sold that amount of gold in Liverpool in 1856, but that did not make the rest

true. The Inquirer and Commercial News

commented that:

He seems a determined young fellow, not very scrupulous, and

capable of lying to any extent. We cannot help regarding it as a more than

suspicious circumstance that the man should have concealed the matter so long,

when the sale of such a secret would have benefited him; while it does not appear

possible that he had the means of visiting the spot himself between the time of

the discovery, and the date of his conviction and transportation some four

years ago.

So Wildman had gained the attention of the authorities,

there was a faint scrap of corroboration from Grey, and by 1864, mails could

travel by steamer to Suez, cross to the Mediterranean by train, and reach

London by steamer in six weeks. Later newspaper reports said the 1857 bullion

sale had been confirmed before the expedition set out, but they set off on

March 2, 1864, just over two months from his original interview, making this

confirmation unlikely. Then again, portions of the route were also linked by

telegraph cables.

If the enquiry and answer went and came partly by

telegraph, an answer might have got back in time, but the high cost of

telegraphy in 1864 makes it improbable that ‘cables’ were sent. It was lucky

for Wildman that they departed when they did though, because later in March, a

letter from the Rev. W. B. Clarke was published in Perth, saying the story was

dubious.

The geologist said there was probably gold in the area,

along with iron ore and copper pyrites. In his opinion, picking up 8 pounds of

gold was unlikely, and he thought Wildman had probably collected copper pyrites

(copper sulfide) instead.

That did not matter: money had been raised, and a small

vessel was sent off, but when they got there, Wildman ‘turned sulky’ and

refused to lead anybody to the gold. Some of the party went ashore and found

good country for farming, but no gold. As punishment for his lack of

cooperation, Wildman was demoted from being an honoured passenger and set to

work as a cook, but he was unbothered.

He was where he wanted to be, in a vessel from which he

could steal a boat and head north to the Dutch East Indies, modern Indonesia.

He was preparing to take off with two boats, when he was caught, placed in

irons, and taken back to Perth.

He probably served out his sentence, with a few extra

years for his naughtiness. Whatever his fate, Wildman disappeared from view,

and the only result was that a party had gone out to satisfy their gold hunger.

Instead, they found good cattle country and saw that there was pearl shell in

the area. Unlike those he hoodwinked, Wildman knew one thing: the promise of gold

blinds men’s eyes to logic and common sense. It is that blindness that makes

gold rushes so possible.

Salting

One quick way to make money from gold was to sell a useless

claim or a worthless mine, but to get people to buy it, you often needed to

‘salt’ the claim or mine. In the earliest days, this practice was called

‘peppering’, but ‘salting’ soon replaced the older name. The victims only had

to see a bit of gold, and they would be hooked.

There were simple tricks, like putting gold dust under

the fingernails when the seller is panning a few samples for the buyer. The

dirt needs to be puddled, squished and squeezed in the water to break up any

lumps of clay, and that, of course, frees the gold under the nails.

Salters who bit their nails could not use that trick,

but they could always spit gold into a pan while watchers were distracted, or

when the panner stood and turned away to examine the dish closely in the

sunlight. Then again, gold dust in the panner’s hair could be dislodged when he

adjusted his hat.

Cunning buyers might try a few pans of their own. Back

when most people smoked, a prepared pipe or cigar could be used to drop gold

pellets into the pan, along with the ash which would wash away. In the end, as

alluvial mining gave way to hard-rock mining, most of the pan tricks died out,

replaced by larger-scale salting of whole mines.

The method that most people have heard about involved

blasting the walls of a mine with a shotgun loaded with gold dust. This trick

was popular for a while but then it was dropped. Firing off a shotgun in an

enclosed space was deafening and it often caused rock falls.

That aside, the method always gave the walls a patchy

appearance which wary would-be buyers knew to look out for. Besides, all the

‘mark’ had to do was clear the salted rock face before taking samples.

Clever operators used ‘stacking’, where rich rock was

brought in. Other crooks would interfere with the samples taken by the

prospective buyer. It was a cat-and-mouse game: if the expert sent the rock up

in a bucket to a trusted assistant at the top of the shaft, a man could lurk in

a drive (a horizontal tunnel), half-way up, and blow gold dust into the bucket

as it went by.

If the expert took bags down into the mine and sealed

them on the spot, he might be sprinkled from above with a rain of gold dust

that would contaminate the samples as they went into the bags. Even if the

sampled ore was taken cleanly and the bags were sealed, there were ways of

getting access to them, and it was always possible to use a confederate in the

assay office.

The best stories are always hard to confirm, but I want

to believe this one, from the Kalgoorlie

Western Argus in 1913. Mind you, no date and no names were given for the

actual coup, which is always a warning signal. It seems that a cunning expert

had come in to test a mine which the owners wanted to sell. He kept the sellers

away from the sampling, before setting off for the nearest township, with his

samples in strong, sealed bags. He went to a hotel, locked the windows and door

of his room and went to dinner.

There were other co-owners of the mine in the hotel, men

he had never met, and they invited him to join them in a game of cards.

Upstairs, the owners he would have recognised got into his room using a master

key, unpicked one of the seams on each of the bags, salted the samples, and

restitched the bags. The expert checked the seals later and found them secure,

so he trusted the results, and the sale went ahead. The new owners spent

another £18,000 on a new mill and a tramway, and started operations. Just ten

feet, three metres in, they hit a body of ore that yielded £80,000 worth of

gold. It was a win all round, but one which must have left the original

shareholders a little saddened!

The Bishop’s nugget

The German traveller

Friedrich Gerstäcker rode out of Sydney to paddle down the Murray River from

Albury to Adelaide in May 1851, just as the gold rush began. He returned by

ship to a changed Sydney—he said the town seemed to be on fire about a

nugget that had just come in, which he called the ‘Robinsonean lump’.

Mr Robinson,

an associate of Sydney’s Anglican Bishop, had been to Sofala, supervising the

building of a church there. The local Bathurst

Free Press and Mining Journal picked up this small fairy tale on 8 November 1851:

Soon the excavations began to assume a depth and size

adequate to the purpose for which they were designed, when, as if the earth

itself resolved to share in the pious work, a nugget of gold was found by—Robinson,

Esq.; and presented to the venerable Bishop, who, delighted with the

circumstance, determined upon its special preservation as a memento of the

sacred occasion.

Sadly, the cunning reporters at Mr Parkes’ Empire soon had the truth of the story: the

nugget had been planted by a practical joker.

Scrammy Jack’s scam

Toby Ryan offered his readers the tale of Scrammy Jack,

probably the only man ever to salt an inn. Let me sound a note of caution: I

commonly describe Toby as unusually

unreliable, and this is not a double negative. He was old when he wrote his

memoirs, and in the days before the internet was even dreamed of, he had no

problem filling in the missing gaps from his imagination, so we need to

double-check his yarns.

‘Scrammy’ was a label usually given to somebody missing

part or all of one hand, and Toby’s ‘John Minighan’, had lost his left hand.

Ryan’s spelling was always a bit eccentric, so this is most probably the same

man as John Minehan. According to Ryan, Jack did good trade for a while at his

inn at Jews Creek on the Mudgee Road, but the nearby goldfield was failing, and

soon the diggers would be moving on. Scrammy Jack hated making a loss, so he

had to get rid of the pub. A man looking for investments—Ryan called him ‘the

mullet’, called in on his way to Mudgee.

Scrammy Jack saw his chance, and when the mullet called

in again on his way back to Sydney, all the local timber-getters and remaining

gold diggers had Jack’s money to spend. The bar did a roaring trade, the mullet

took the bait, and paid £1200 for a property which, with contents, was worth

only £100, Ryan said.

Now for the truth tests. First, there is a mention in

the Sydney Morning Herald on 22

August 1851 of “Scrammy Jack, meaning John Minehan” in a Bathurst court case

from 1851, where Scrammy Jack was named as the source of an allegedly stolen

ring. After that, the evidence comes from the pages of the Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal.

A man called John Minehan gained a licence by a majority

of one in April 1855, and established the Ben Bullen Inn. It was a small majority,

which suggests that some of the magistrates who sat as a panel and decided on

licences had their doubts about the would-be publican. Still, he got enough

nods, and got his pub.

Minehan advertised for a sober cook in June, 1855 and

praised his stockyards and wines, spirits and ales list in other

advertisements, also in June, but by December, the licence was transferred to a

Mr Bird. So Toby Ryan’s story seems to stand up.

If one asked Toby if this story was true, be probably

would not have to smile disarmingly as he crossed his fingers behind his back

and muttered “It’s true that it’s a story!”

Getting rich from gold.

While Australia became

rich and benefited from reaping an adventurous population, only a few seekers

came out ahead on their efforts. Those few became wealthy, some did well, a

larger group broke even, but more of them just went broke, beaten by trying to

stay alive on the goldfields.

Bullockies had no cares: when a wagon drawn by sixteen

bullocks, became bogged in King Street, Melbourne, Claus Gronn saw calm and

unperturbed bullockies, who let the sixteen beasts rest whilst they took a swig

from their billy-cans. He said these were full of she-oak, the popular name for

colonial beer, named after the locally-made casks. When you are well-paid,

taking a break with friends was good, and those men were very well-paid.

The place names that we see on old goldfields tell us a

tale. There is a Starvation Flat in California, and a Starvation Creek in

Victoria, but most of Australia’s 1850s goldfields were close enough to food

sources that genuine starvation was never a threat. Sometimes, finding the

money to pay for the food was harder. So was finding safe food!

Some diggers took their own supplies to the goldfields.

Those who could not cook damper could buy “ship’s biscuit”, hard dried pellets

of “bread stuff”, hard enough almost to use as bricks to build a house. In

1851, there was little understanding of nutrition, but everybody who had

travelled to Australia by ship knew that ship’s bread, otherwise called hard

tack, or biscuit, would keep you alive. Bread was, after all, the staff of

life, they would say.

The successful diggers wanted real bread and some of

them could afford to pay for it, so the smart bakers followed their customers.

By the end of 1851, the Turon River had bakeries and bakers’ carts, delivering

bread at 9d. for a fresh two-pound loaf. In 1855, George Wathen said an

Adelaide baker who traded on the Victorian goldfields for 18 months, had sold

his bakery and sent 50 pounds weight of gold back to Adelaide.

Doctors and

undertakers also turned a healthy profit, because the goldfields were unhealthy

places. Doctors’ fees were ten shillings for a consultation at their own

tent; a “visit out” would cost from one to ten pounds, according to time and

distance.

Fresh fish were soon being sent from the Murray River to

the Victorian goldfields. Caught in Moira Lake near Barmah, the fish went by

boat to Echuca no later than 9 p.m. on Friday night, to be carried by cart to

Bendigo, 7 or 8 hours away, in time for the early morning market on Saturday.

By 1855, the ingenious fishermen knew how to keep their

fish alive when they caught them early in the week. They would push a strong

hook through the jaw, using an equally strong cord to tether the fish, alive

and fresh in the river, until it was time to load the cart.

Those who traded horses and working oxen in Melbourne

did well. The seller paid five shillings to enter a beast on the sale list,

then after the sale, the purchaser paid ten per cent, for a guarantee that the

animal was not a stolen one, while the vendor had ten per cent deducted from

the purchase-money as a commission. As the five shilling entrance fees paid the

yard expenses of the day, the 20% was clear profit.

In 1853 Melbourne, a carpenter could expect 20 shillings

per day, a blacksmith 18 shillings and a road labourer 10 shillings a day. A

married couple could expect £80 a year with rations, and a shepherd £35, while

a bullock driver, with rations, got £3 per week. A seaman on a coaster got £9

per month, said William Westgarth.

Being a gold

digger who was sinking shafts was dangerous. One reporter wrote at the end of

1851 that nobody would ever tunnel through the earth to win coal, unless they

knew about mining.

Yet, he said,

miners on the Turon recklessly drove shafts and tunnels into the soil, seeking

gold, and several accidents had already happened. A few experienced miners in

the area used proper supports, but these wise folk were rare.

Less than two

months later, on 12 February, 1852, at Devil’s Hole Creek near Mudgee, an

innkeeper named James Broderick was mining with two other men. He went to dig

in the “mine” while his colleagues worked the cradle. They came back for more

earth, and found that two or three tons of soil had fallen in on Broderick, who was dead. He was survived by a wife

and family.

On 15 March,

another collapse on the same field killed John Long, though his partner,

Frederick Tucker was dug out alive. The best way to prevent cave-ins was to